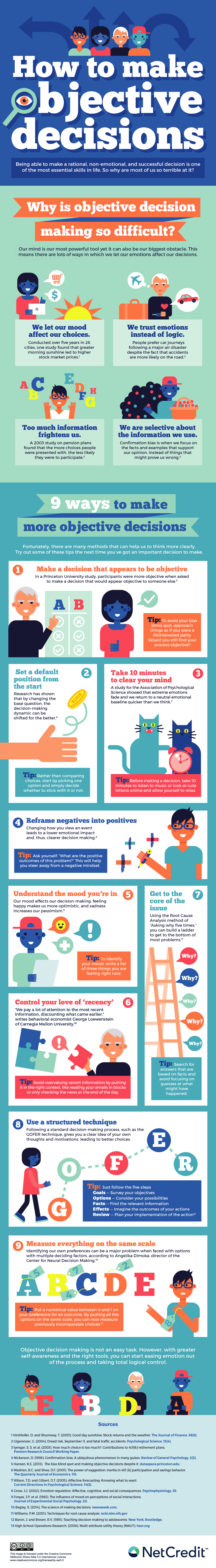

We make decisions every day; some are very important, others – less so. They range from what to have for lunch or how to spend your weekend to leaving your job or having a child. It’s surprising then how little attention we pay to one of decision-making’s biggest variables: our own emotions.

Consistency is the key

We may not notice it at the time, but how we feel has a big impact on the decisions we make. So, how do we find a level of personal consistency, where we never look back and cringe at our choices? The key is to develop our powers of objective decision-making.

Like any piece of seemingly simple advice, this is easier said than done. Consistently making non-emotional and rational choices takes a lot of practice and self-reflection. It will be worth it however, as harnessing the power of objective decision-making can have huge positive effects.

Learning to deal with emotions

The first step is recognizing your current emotional state and how this could possibly affect the choice you are about to make. Studies show that stock markets are higher when the sun shines in the morning and that people make irrational decisions when fearful. Emotions are not always the enemy but they can make you do things you might not otherwise do if you were at your general emotional baseline.

Once you are in a mental space where you know if you are angry, fearful or happy there are several positive actions you can take to lessen the impact these emotions have. Our helpful tips will give you the tools you need to keep your emotions in check while you decide what’s going to happen next.

Taking time to follow a process

Finding the right structured process to evaluate a decision or even just taking some time to allow the intensity of an emotion to subside is a move in the right direction. Learning to do these things on a regular basis can free us from the tight grip our emotions hold on our behavior.

We can’t tell you which sandwich to pick or whether or not to dump your partner. We can help you to get into the right frame of mind to make the big decision however. They won’t always be the right ones, but at least you’ll know that you made it to the best of your knowledge at the time!

Source

1 Hirshleifer, D. and Shumway, T. (2003). Good day sunshine: Stock returns and the weather. The Journal of Finance. 58(3).

2 Gigerenzer, G. (2004). Dread risk, September 11, and fatal traffic accidents. Psychological Science. 15(4).

3 Iyengar, S. S. et al. (2003). How much choice is too much?: Contributions to 401(k) retirement plans. Pension Research Council Working Paper.

4 Nickerson, D. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology. 2(2).

5 Hansen, K.E. (2013). The bias blind spot and making objective decisions despite it. dataspace.princeton.edu.

6 Madrian, B.C. and Shea, D.F. (2001). The power of suggestion: Inertia in 401 (k) participation and savings behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 116.

7 Wilson, T.D. and Gilbert, D.T. (2005). Affective forecasting: Knowing what to want. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 14(3).

8 Gross, J.J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology. 39.

9 Forgas, J.P. et al. (1983). The influence of mood on perceptions of social interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 20.

10 Begley, S. (2014). The science of making decisions. newsweek.com.

11 Williams, P.M. (2001). Techniques for root cause analysis. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

12 Baron, J. and Brown, R.V. (1991). Teaching decision making to adolescents. New York: Routledge.

13 High School Operations Research. (2006). Multi-attribute utility theory (MAUT). hsor.org.